Suspension of the Indus Water Treaty and Its Implications

Suspension of the Indus Water Treaty and Its Implications Table of Contents Explained: Suspension of the Indus Water Treaty and Its Implications Suspension of the

Debashree Mukherjee, India’s Secretary of Water Resources, on Thursday (April 24, 2025) wrote to her Pakistani counterpart, Syed Ali Murtaza, that India was keeping the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) in abeyance with “immediate effect” following the terror attack in Pahalgam, which claimed the lives of 26 civilians. In response, the Pakistan Prime Minister’s office condemned the move as an “act of war” and announced a series of retaliatory diplomatic measures, including the suspension of the 1972 Simla Agreement.

For several years, India had sought to renegotiate the Indus Waters Treaty. Now, the suspension of the treaty serves the dual purposes of raising the costs associated with the terrorism that Pakistan funds and exports, as acknowledged by its defense minister, and advancing India’s long-term strategy to reshape a deal that has been regarded as unfair for years.

Following the Cabinet Committee on Security’s (CCS) meeting chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the aftermath of the Pahalgam attack, India’s Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri announced a slew of punitive measures directed at Pakistan. Still, one stood out from the rest: holding the Indus Waters Treaty in abeyance.

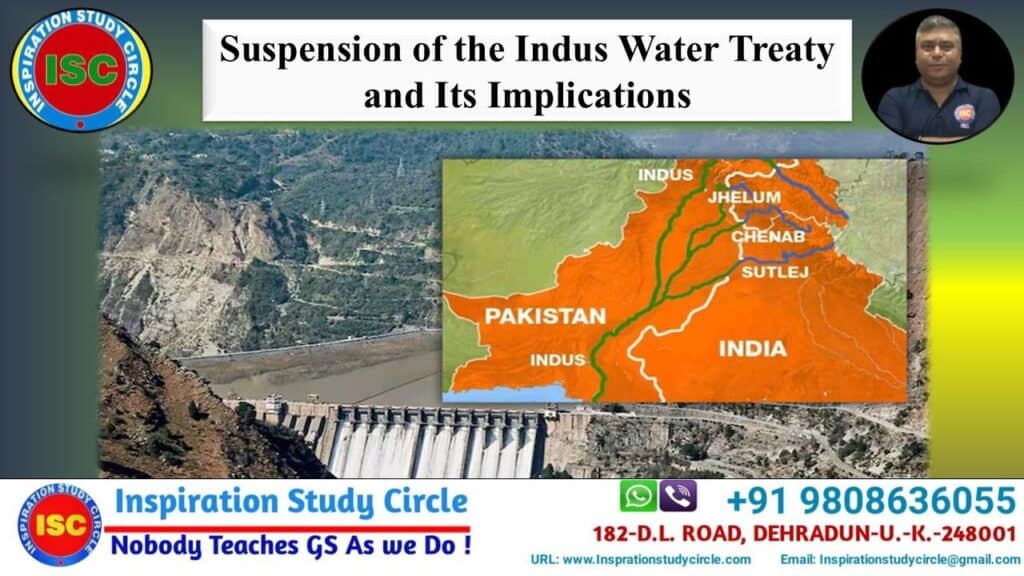

The Indus Water Treaty (IWT) is a water-distribution treaty between India and Pakistan, arranged and negotiated by the World Bank, to use the water available in the Indus River and its tributaries. It was signed in Karachi on 19 September 1960 by then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and then-Pakistani President Ayub Khan.

The Treaty gives India control over the waters of the three ‘Eastern Rivers’—the Beas, Ravi, and Sutlej, which have a total mean annual flow of 41 billion cubic metres. Control over the three ‘Western Rivers’—the Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum, which have a total mean annual flow of 99 billion cubic metres, was given to Pakistan.

The treaty allows India to use the water of Western Rivers for limited irrigation use and unlimited non-consumptive uses such as power generation, navigation, floating of property, fish culture, etc. It lays down detailed regulations for India in building projects over the Western Rivers. The treaty’s preamble recognises each country’s rights and obligations for the optimum water use from the Indus System of Rivers in a spirit of goodwill, friendship, and cooperation. Though the treaty is not directly related to national security, Pakistan, being located downstream of India, fears that India could potentially cause floods or droughts in Pakistan, especially during a potential conflict.

During the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948, control over the river system’s water rights was the focus of an Indo-Pakistani water dispute. Since the ratification of the treaty in 1960, most disputes have been settled via the legal framework provided by the treaty, despite several military conflicts having occurred between the two countries. The treaty was suspended for the first time by the Government of India on 23 April 2025, following the 2025 Pahalgam attack.

The Indus Waters Treaty is considered one of the most successful water sharing endeavors in the world today, even though analysts acknowledge the need to update certain technical specifications and expand the scope of the agreement to address climate change.

The waters of the Indus system of rivers begin mainly in Tibet and the Himalayan mountains in the states of Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir. They flow through the states of Punjab and Sindh before emptying into the Arabian Sea south of Karachi and Kori Creek in Gujarat.

The partition of British India, based on religion, not on a geographical basis, created a conflict over the waters of the Indus basin. The newly formed states were at odds over how to share and manage what was essentially a cohesive and unitary network of irrigation. Furthermore, the geography of partition was such that the source rivers of the Indus basin were in India. Pakistan felt its livelihood threatened by the prospect of Indian control over the tributaries that fed water into the Pakistani portion of the basin. Where India certainly had its ambitions for the profitable development of the basin, Pakistan felt acutely threatened by a conflict over the main source of water for its cultivable land.

During the first years of partition, the waters of the Indus were apportioned by the Inter-Dominion Accord of May 4, 1948. This accord required India to release sufficient water through existing canals to the Pakistani regions of the basin in return for annual payments from the government of Pakistan. The accord was meant to meet immediate requirements and was followed by negotiations for a more permanent solution. However, neither side was willing to compromise.

Pakistan wanted to take the matter at that time to the International Court of Justice, but India refused, arguing that the conflict required a bilateral resolution.

In 1951, David Lilienthal, formerly the chairman of the Tennessee Valley Authority and the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, visited the region and realized the tension between the two countries. India and Pakistan were on the verge of war over Kashmir. There seemed to be no possibility of negotiating this issue until tensions abated. One way to reduce hostility was to concentrate on other important issues where cooperation was possible.

He suggested that the World Bank should use its good offices to bring the parties to an agreement and help in the financing of an Indus Development program. Lilienthal’s idea was well received by officials at the World Bank (then the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development) and subsequently by the Indian and Pakistani governments.

Eugene R. Black, then president of the World Bank, made a distinction between the “functional” and “political” aspects of the Indus dispute.

The IWT was signed by both countries on the same day in 1960, applicable with retrospective effect from 1 April 1960. After signing the IWT, the then-prime minister Nehru stated in the parliament that India had purchased a water settlement. The grants and loans to Pakistan were extended in 1964 through a supplementary agreement.

Pakistan raised concerns with the World Bank regarding India’s new dam project on the Chenab River, saying that it is not in conformity with the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) and argued that India could use these reservoirs to create artificial water shortage or flooding in Pakistan.

In 2019, in the aftermath of the Pulwama attack, the Union Minister for Water Resources and a senior leader in the ruling party BJP Nitin Gadkari said that all water flowing from India will be diverted to Indian states to punish Pakistan for an alleged connection to the attack, something which the Pakistani Government denied and condemned. Union Minister of State for Jal Shakti Rattan Lal Kataria said that “every effort is made” to stop the flow of water downstream from the three assigned rivers.

In 2023, India officially notified Pakistan to renegotiate the treaty, alleging that it was repeatedly indulging in actions that are against the spirit and objective of the treaty. Pakistan responded to the notice issued by India, stating Pakistan cannot take the risk of abrogating IWT being a lower riparian party, and expressed its desire to adhere to the procedures stipulated in the IWT.

In September 2024, India formally sought review of the Treaty, and at the same time, Pakistan reaffirmed the importance of the agreement and requested that India continue to comply with the provisions of the Treaty.

On March 1, 2025, India officially stopped the flow of Ravi River water into Pakistan after 45 years of delays, marking a significant shift in the region’s water dynamics.

On 23 April 2025, following a targeted terrorist attack in Baisaran Valley of Pahalgam, Jammu and Kashmir, the Government of India, in a meeting of the Cabinet Committee on Security, declared the suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty with Pakistan, citing national security concerns.

By holding the Indus Waters Treaty in abeyance, India has seized a moment that it had been looking for and is now addressing the shortcomings of the treaty as well as mounting a response to the Pahalgam attack, quoted Prof Medha Bisht of the Department of International Relations, South Asia University (SAU), Delhi.

In the immediate future, despite Pakistan’s dire reaction, the taps in the country are not going to run dry. With the Indus treaty on hold, India is playing a long game to corner Pakistan. However, Pakistan’s framing of the treaty’s practical suspension is more about rallying people around the flag instead of addressing the long game that, anyway, Pakistan can do little about — the nation is held hostage by its geography.

Under the Indus treaty, India had been sharing information related to the river with Pakistan in advance, including the flow of water and any major release or withholding of water, so that Pakistan could make appropriate arrangements. With the treaty in abeyance, such information-sharing has stopped.

While India cannot stop water from flowing into Pakistan completely, it can tamper with the flow that can affect the availability of water for agriculture, hydropower generation, and other purposes at times of high requirement, such as in summer.

Reports further say that the government is working on a legal strategy to address legal challenges that Pakistan or the World Bank, which is also a party to the treaty, may mount at international forums.

Suspension of the Indus Water Treaty and Its Implications Table of Contents Explained: Suspension of the Indus Water Treaty and Its Implications Suspension of the

ISC – Success Story UPSC 2024 Table of Contents UPSC CSE 2024-25 Results Out – A Prosperous Success Story for the Inspiration Study Circle ISC

UPSC 2024 – Result Expected on 22nd April 2025 Table of Contents UPSC 2024 – Result Expected on 22nd April 2025 UPSC 2024 – Result

Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana – Completes 10 Years Table of Contents Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana – Completes 10 Years Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana – Completes

Classroom Program for UPSC 2026- 27 Table of Contents Inspiration Study Circle Classroom Program for UPSC 2026- 27 Greetings Civil Service Aspirants! Inspiration Study Circle

Civil Services after 12th: UPSC Foundation Course Table of Contents Civil Services after 12th: UPSC Foundation Course Inspiration Study Circle, the best IAS/PCS coaching institute